Morality through achieving goals jointly

Instrumental normativity becomes moral normativity when the goal is achieved jointly.

Morality could be described as the intrapersonal, interpersonal, and collective normative structures that arise when people collaborate towards a joint goal, necessarily relying on one another, and taking the risk of placing their fates in each others' hands.

In other words, morality is the normativity internal to the collaborative group, team, or partnership.

Helping a stranger in the street

It can be argued that when we help a stranger in the street, for example, we are

not collaborating towards a joint goal. This is true in a way. My (proximate) goal

is one-

It may also be argued that when I experience a proximate motivation to help a suffering

stranger, our joint proximate goal is win-

Types of morality

If morality is the normative structure that arises when we collaborate towards a joint goal, then we can define a morality with: 1) a goal; 2) a method of achieving that goal. Each definition forms a moral domain and generates moral values.

|

Goal |

Win- |

Reproduction / mate acquisition and retention |

Reproduction / mate retention |

Reproduction / raising children |

Inclusive fitness |

|

Method of achieving goal

|

Cooperation |

Patriarchy |

Pair- |

Parenting |

Family values and duties |

|

Moral principles are (MAC)1 |

Solutions to challenges to win- |

Solutions to challenges to mate acquisition and retention |

Solutions to challenges to mate retention |

Solutions to challenges to raising children |

Solutions to challenges to inclusive fitness |

|

Moral principles are (GM)2 |

Ideal ways to cooperate |

Ideal ways to be patriarchal |

Ideal ways to pair- |

Ideal ways to parent |

Ideal ways to carry out family duties and values |

|

Virtues |

Moral principles |

Moral principles |

Moral principles

|

Moral principles

|

Moral principles

|

|

Vices |

Breaches of moral principles |

Breaches of moral principles |

Breaches of moral principles

|

Breaches of moral principles

|

Breaches of moral principles

|

1: MAC = Morality-

2: GM = Goals / Methods model of morality (Perry, 2022)

So we have, for each moral domain:

moral principles = ideal ways to (method) = ideal ways to (achieve goal G)

= solutions to challenges to (achieving goal G)

Morality does not equal collaboration

Importantly, morality does not equal achieving a goal jointly. Morality does not equal, for example, cooperation, since cooperation can be used to commit evil. Morality is the internal normativity that arises within a group, team or partnership when it seeks to achieve a goal jointly. So, Nazis could be moral towards each other (loyal, reciprocal, etc.) while being unethical towards everyone else.

Internal features of morality (sources of normativity)

Interdependence shapes and directs moral normativity.

All internal features of morality are sources of normativity because they are all in the service of achieving the joint goal; their purpose is to help to achieve the joint goal; normativity is the pressure to achieve goals; and so, all internal features of morality are sources of the pressure to achieve the joint goal.

- Instrumental normativity = pressure to achieve goals

- Joint goal

- Joint commitment

- That for which we may be held accountable by others

- Mutual risk and strategic trust

- Promoting, enforcing good behaviour according to norms

- Discouraging, preventing bad behaviour according to norms

- Partners

- Partner choice by reputation and cooperative identity

- Partner control

- Roles and their ideal normative standards

- Duty: sense of responsibility to (respected and valued) other partners to uphold ideal normative standards

- A set of moral norms (general role ideals that apply to any collaboration alike, with this goal and method)

- A set of moral values (policies for achieving moral/joint goals)

- A set of moral virtues (ideal performance of norms)

- A set of moral vices (sub-

standard performance of norms: to be avoided) - Intrapersonal, interpersonal and cultural levels

Value and moral values

A policy is a coordinated pattern of behaviour.

A value is either: 1) a utilitarian good; 2) a policy for achieving a goal G.

A moral value is a policy for achieving a moral goal: i.e., a joint goal G.

A moral value is the same thing as a moral principle: valuable in itself because it is a policy for achieving a joint goal.

If a moral value is a policy for achieving G, jointly, then a moral principle is a method, within a moral domain defined by an overall method, of achieving some overall G jointly.

So, if cooperation is an overall description of ways to achieve win-

A trait can only evolve if it benefits the self.

Tomasello et al. (2012) propose two stages of human evolution: living in small groups from around 2 million years ago, and larger tribal groups from around 150,000 years ago. From around 10,000 years ago, we began living in large mixed city states.

It may be that fairness (as distributive justice) and reciprocity evolved in stages

from “looser” in small free-

The Golden Rule may be defined as compassionate “imagine self in position of other”

perspective-

The goal of patriarchy is ultimately reproduction at men's convenience, and proximately,

mate acquisition and retention by men using the control and suppression of women

(see Perry, 2021:104). (The alternative, egalitarian male reproductive strategy

is to make themselves into as ideal mates as possible.) Patriarchy is constructed

collectively, on a society-

Feminism, the egalitarian assertion of rights for women as well as men, is a necessary female resistance of patriarchy, and would not need to exist without patriarchy. Among the great apes, those species with the strongest “sisterhood” or most effective solidarity between females are the most free from patriarchy in males. This is, bonobos (de Waal, 1998, Smuts, 1995; see Perry, 2021:106).

Right and wrong

In what sense does evolutionary ethics say that things are right and wrong?

Interpersonal behaviour can be right or wrong according to this or that moral principle

– whether helping in response to need; the Golden Rule; obedience in women; faithfulness

to a pair-

Hence, behaviour can be right according to moral values A, B, and C; but wrong according to moral values D, E, and F. Behaviour is rarely 100% one or the other: ethical or immoral.

As a standard method for achieving a joint goal, the moral value thus forms an impartial

external arbiter or standard by which to judge moral justice and ought-

Morals and ethics

We define morality as the normativity internal to the cooperative unit. We define ethics as behaviour that conforms to the “best” of that normativity: that positively correlates with moral values; “the good”.

We hypothesise that overall, the most important ethical value, in the minds of typical

human beings, is compassion, in the form of the bodily well-

The morality between groups is another matter: how groups interact morally with each other. We may observe that they have higher tendency towards competition than in the interpersonal relations of individuals. Human groups living and interacting together as whole entities may thus be more like chimpanzees: social but not very cooperative; competitive, strategic, and Machiavellian (Tomasello, 2016).

Evolved moral domains and moral values

1. Cooperation for win-

Interpersonal / small groups

- altruism

- fairness

- reciprocity

- the Golden Rule

- autonomy

- personal loyalty

- mutual respect

- conflict minimisation and avoidance

Collective / large groups

- social order

- authority ranking

- tradition

- social norms

- group loyalty

2. Patriarchy for reproduction, at males’ convenience, through mate acquisition and retention (cooperativised as social norms)

- assertion of the "superiority" and dominance of men

- assertion of the “inferiority” and subordination of women

- female obedience to men

- female chastity and modesty

- women as property of men

- sexual exclusivity in women but not necessarily in men

- men providing resources for “their” women

- men physically protecting women from other marauding men

- respecting another man’s “ownership” of his female “property”

3. Pair-

- loyalty and faithfulness on both sides to the pair-

bond - respecting another’s pair-

bond

4. Parenting for reproduction through raising children successfully

- proper care by parents for children

- loyalty of children towards parents

5. Family morality for inclusive fitness of individuals

- preferentially helping family members

- loyalty towards the family

- solidarity with the family

- maintaining the reputation of the family

Loyalty

Loyalty is a result of the giving of compassion – altruism – helping in response

to need – on at least one occasion, when it really mattered. Loyalty can be to a

person, people, one’s group or coalition, one’s family, one’s pair-

Loyalty could be described as a genuine and sincere commitment to help. As a gift

or exchange of compassion, we would expect to see it within the moral domains of

cooperation for win-

Family, compassion, and two kinds of fitness benefit

Because we need them to be alive and well, we wish to help those who represent fitness value for us: whether utilitarian or genetic.

Family loyalty is a result of bestowing a different kind of fitness than that given in compassion. I am loyal to family members because they are helping to ensure the survival and potential reproduction of some of my genes. This is described in Hamilton’s Rule:

“I will help you when” r × B > C

“I will help you when the amount by which it benefits the genes we share is greater than the cost I incur in helping you”.

B = your benefit

r = coefficient of relatedness

> is greater than

C = my cost

The kind of fitness benefit bestowed in compassion is to put the right conditions

in place in the other person for the pressure to thrive to do its work in them: as

a flower that we look after in the garden grows strong and healthy because we give

it the right conditions it needs. We feel a desire to help those whose value benefits

us. We may call it a form of reciprocity: “long-

altruists pay a cost c which benefits a recipient by b. Then, unlike in reciprocal altruism where the recipient actively benefits the original altruist, the altruist gains secondarily as a function of the beneficiary's gain. Denoting as s the altruist’s stake in the recipient’s benefit, we obtain the expression:

Roberts, 2005

“I will help you when” s × B > C

B = your (increased) well being

s = my stake in your (overall) well being

> is greater than

C = my cost in helping you

Moral purity

Moral purity is treated as a separate moral “foundation” by Jonathan Haidt (2013) and others. However, we propose that purity is “about” the other evolved moral foundations: it is a quality that may apply to any of them.

Purity is a property of sacred values – things that are treated as having infinite value (see Perry, 2021:225). Now, all of the evolved moral foundations have either reproduction or mutual fitness as their goals. Reproduction and fitness are of infinite value, because the DNA molecule reproduces. Hence, any of the evolved moral domains and their values can be, and is, regarded as sacred.

Sacred principles can be “polluted” by their antitheses: selfishness, and “dark” behaviour. “Dark” behaviour means to thrive at the expense of others, whether negligently or deliberately (see Perry, 2021:182).

Other forms of morality (goals/methods)

There are other forms of morality than the evolved ones: for example, religion, and medical ethics. In religion, the goal is “serving God”, and the method of achieving it is “religious practice”. This involves all the standard features of morality/sources of normativity that we see in evolved morality. Since it constitutes a complete system for living, it incorporates the morality of the day (or that from historical times). Medical ethics has “patient welfare” as its goal, and “ethical medical practice” as the method of achieving it.

References

Curry, Oliver Scott; Daniel Austin Mullins; and Harvey Whitehouse – “Is It Good to

Cooperate? Testing the Theory of Morality-

Haidt, Jonathan – “The Righteous Mind – why good people are divided by politics and religion”; Penguin Books, London 2013

Perry, Simon – “Understanding morality and ethics” (2021); https://orangebud.co.uk/Understanding%20morality%20and%20ethics.pdf

Perry, Simon – “Types and features of morality” (2022); https://orangebud.co.uk/types.html

Pick, Cari M – “Fundamental social motives measured across forty-

Roberts, Gilbert – “Cooperation through interdependence”: Animal Behaviour, 2005, 70, 901–908 https://www.academia.edu/28485879/Cooperation_through_interdependence

Smuts, Barbara – “The Evolutionary Origins of Patriarchy": Human Nature, Vol. 6,

No. 1, pp. 1-

Tomasello, Michael; Alicia P Melis; Claudio Tennie; Emily Wyman; Esther Herrmann – “Two Key Steps in the Evolution of Human Cooperation – The Interdependence Hypothesis” – Current Anthropology, vol. 53, no. 6, Dec 2012

Tomasello, Michael – “A Natural History of Human Morality”; Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA 2016

Tomasello, Michael – “Becoming Human – a theory of ontogeny”; Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA 2019

de Waal, Frans B M and Frans Lanting – “Bonobo – the forgotten ape”; University of California Press, Berkeley CA 1998

de Waal, Frans B M – “How Animals Do Business” – Scientific American, April 2005

Foundations of evolutionary ethics

Evolutionary origin of normativity

The explanatory stopping-

We hypothesise that the ancient first-

Hence, those alleles that competed to reproduce could survive in the population long

enough to reproduce the next generation. The finiteness of the resources in the

environment, sets up a competitive evolutionary pressure to reproduce, and thereafter,

all organisms experience an internal pressure to reproduce (or at least, according

to Freud’s Eros theory, to go in that direction (see Perry, 2021:16-

Normativity

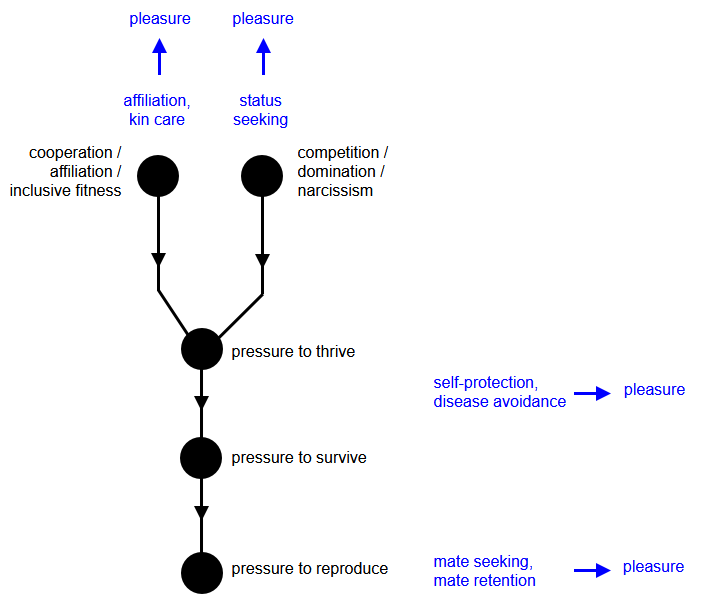

Key to diagram

The pressure to thrive depends on the pressure to survive, which depends on the pressure to reproduce.

Cooperation and competition are two alternative ways to thrive, survive and reproduce:

to achieve fitness. Cooperation results in win-

Pick et al. (2022) identify a number of universal human motivations, that are “high

in fitness relevance and everyday salience”: self-

When a fitness goal is approached or achieved, pleasure is the result. When a fitness goal is hindered or fails to be achieved, the result is pain. Accordingly, Freud’s Pleasure Principle states that there is a pressure to seek pleasure.

“Inclusive fitness” refers to the fitness of: 1) myself and my genetic relatives; 2) myself and the people who help me (to maintain my fitness).