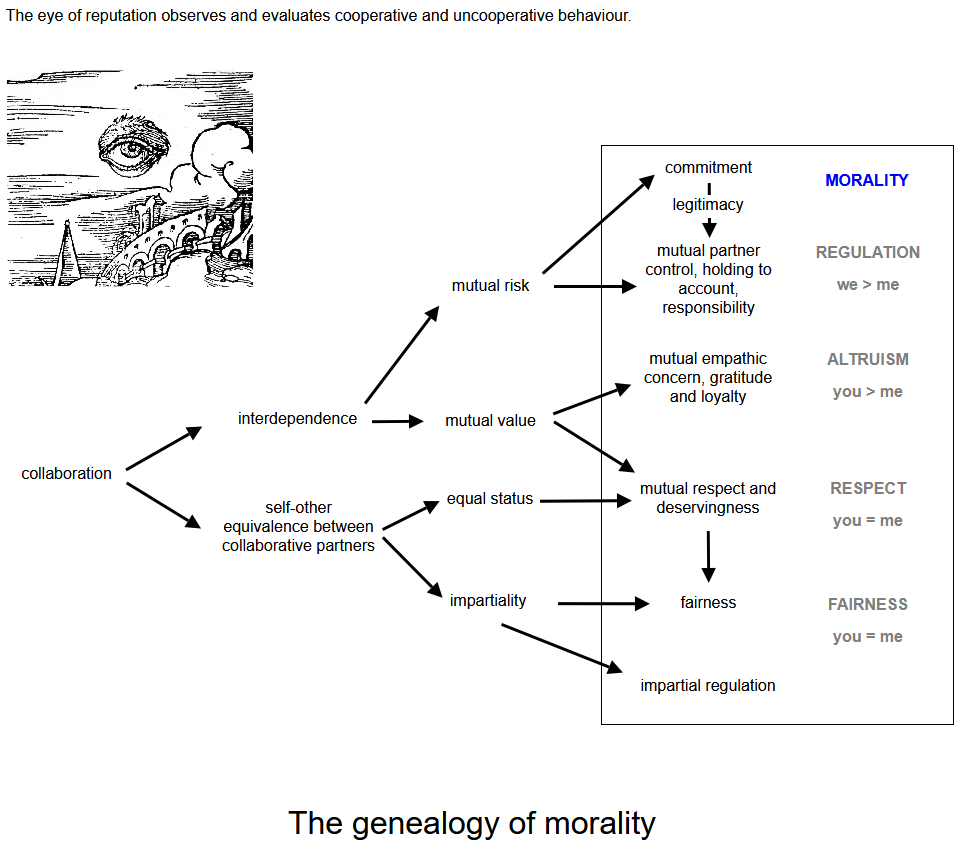

How collaboration gives rise to morality

Collaborating towards a joint goal gives rise to an understanding of mutual dependence

and self-

* There are other kinds of evolved morality, namely: parenting, pair-

The proposal is that collaborating towards joint goals, with its accompanying evolved psychology, gives rise to the behaviour called morality, and its accompanying evolved psychology.

Dual-

Each partner, “you” and “I” is an agent with his or her own will and purpose. When they act and think intentionally together, they form a joint agent “we”, with joint thinking and joint goals, from which benefits are to be maximised all round.

The joint agent “we” consists of its individual partners “I” and “you”. The perspective

of the joint agent “we” is a “bird’s eye view” where it sees fixed roles with interchangeable

people filling them. Each partner has their own role, and perspective on the joint

goal, and their own goals: sub-

To coordinate our thinking and intentionality, I may take your perspective, as you may take mine, on the collaboration.

The joint agent “we” governs you and I, so that I govern myself, I govern you, and you govern me, on behalf of “us”.

We can break down the “road map” of how collaboration produces morality into its elements, and the links between them, and define the unfamiliar terms and concepts.

(1) collaboration

Engaging in joint or collective activity with others for mutual benefit.

(2) interdependence

Depending on one another: I need you, and you need me; I depend on you, and you depend on me. Symbiosis.

(3) self-

Partners are equivalent in several ways:

- each is equally a causative force in the collaboration: each is equally necessary and responsible for what is done.

- partners are interchangeable within roles, in that each role could in principle be played by any competent partner.

- role ideals are impartial and apply equally to anyone who would play a particular role. Hence, each person's ego is equally constrained, and so, each is equal in status in this sense. None of us is free to do what we like, within the collaboration.

(4) mutual risk and strategic trust

I depend on you (2). What if you let me down, and fail to collaborate ideally, and we do not achieve our goal? There is mutual risk, because each depends on the other, and each may be weak and fallible. In order to get moving, in the face of risk, it is necessary for each partner to trust the other “strategically”: rationally and in one’s own best interests.

(5) mutual value

Because each partner needs (2) and benefits (1) the other, each partner values the other.

(6) equal status

Self-

(7) impartiality

The joint agent “we” governs every partner equally and impartially, since each partner is equivalent and equal (3).

(8) commitment

To reduce mutual risk (4), partners make a commitment to each other: they respectfully

invite one another to collaborate, state their intentions, and make an agreement

to achieve X goals together. This commitment may be implicit -

(9) legitimacy of regulation

Because we agreed to collaborate (8), we agreed to regulate ourselves in the direction of achieving the joint goal. The agreement gives the partners a feeling that the regulation is legitimate: proper and acceptable.

(10) mutual partner control, holding to account, responsibility

Mutual risk (4) and legitimacy of regulation (9) lead to partners governing each other and themselves in the direction of achieving the joint goal. This regulation takes the practical forms of:

- partner control -

partners govern each other through correction, education, “respectful protest”, punishment, or the threat of exercising partner choice - finding a new partner. - holding to account -

I accept that I may be held to account for my behaviour, and you accept that I may hold you to account for your behaviour. - responsibility -

the legitimacy tells me that I “should” be an ideal collaborative partner to you. Hence, I feel a sense of responsibility to you not to let you down in any way, and to see the collaboration through, faithfully, to the end.

(11) mutual empathic concern, gratitude and loyalty

If I need you and depend on you (2), I therefore value you (5) and feel empathic concern for your welfare. I am likely also to feel gratitude and loyalty towards you.

(12) mutual respect and deservingness

If I value you (5) and consider you an equal (6), and we are working together towards joint goals (1), then I am likely to feel that you deserve equal respect and rewards as myself.

(13) fairness

Because you are equally respected and deserving as myself (12), and we are making impartial judgements of behaviour and deservingness (everyone is treated the same regardless of who they are) (7), the only proper result is one of fairness where each partner is rewarded on some kind of equal basis.

(14) impartial regulation

The regulation of “us” (8, 9, 10), by you and I, and the regulation of you and I by “us”, is impartial because we are all equivalent (3).

BASIC MORALITY

Regulation (we > me)

This formula, “we is greater than me”, indicates that the joint agent “we” or “us” is ruling over “you” and “I”. I govern myself, and I govern you, and you govern me, in the direction of the joint goal, on behalf of “us”, legitimately and impartially.

Altruism (you > me)

This formula is about temporarily putting the interests of others above my own, in order to help them, out of charity, gratitude, loyalty, obligation, etc.

Fairness, respect (you = me)

Equality is the basis of fairness, in two ways: 1) egalitarianism is necessary for fairness in that bullies cannot share fairly: dominants simply take what they want from subordinates, who are unable to stop them; 2) deservingness is decided on some kind of equal basis, whether in equal shares, equal return per unit of investment, equal help per unit of need, etc.

“The eye of reputation” observes and evaluates cooperative and uncooperative behaviour

“Reputation” is shorthand for a number of related concepts:

- my opinion of myself as a cooperator and moral person (personal cooperative or moral identity)

- the opinion of my past or present collaborative partners of myself as a cooperator and moral person (cooperative identity)

- my public reputation, the opinion of the world at large of myself as a cooperator and moral person (public moral identity, reputation)

The world, and my collaborative partners, are always monitoring me and evaluating

my performance as a cooperator and moral person. In turn, through self-

According to our reputation or cooperative identity, we may be chosen or not chosen as collaborative partners (partner choice). This can have important consequences as we all need collaborative partners in life. Hence, reputation and partner choice form the “big stick” that ultimately turns my sense of responsibility to be an ideal partner (10), into an obligation, if I know what is good for me.

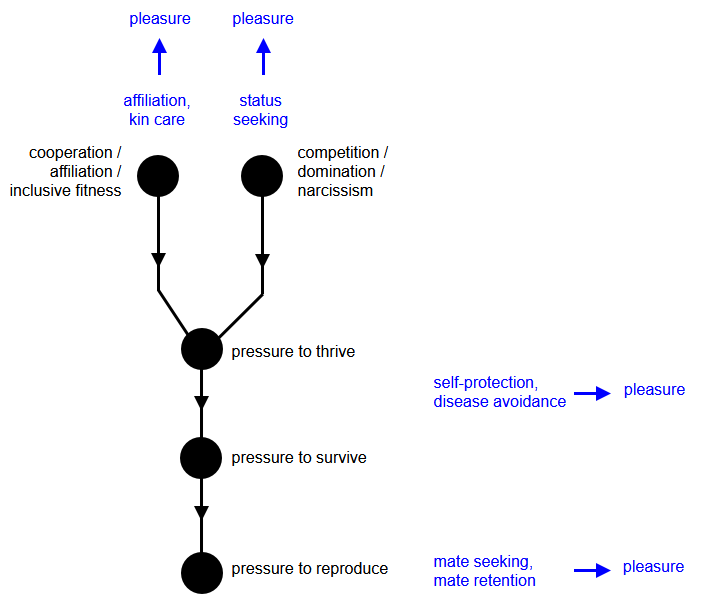

BASIC NORMATIVITY

Normativity is defined as the pressure to achieve goals. The diagram above connects with the structure of normativity (see diagram below). We may be socially normative (achieve our goals socially) in two ways: cooperatively, with others, to mutual benefit; and competitively, at the expense of others. There is also individual action which doesn't affect anyone else, and so is neither cooperative nor competitive.

THE STRUCTURE OF INSTRUMENTAL NORMATIVITY

In the diagram below, cooperation and competition are the two ways to thrive, survive and reproduce involving other people. The black “down” arrows mean “depends on, is a result of”, and the words in blue represent evolved drives, the achievement of which produces pleasure.

References:

Perry, Simon -

Tomasello, Michael -