Response to an evolutionary contractualist theory of morality

This article is a response to the evolutionary contractualist model of morality as

set out in the paper by Jean-

Joint agreements are a necessary part of collaboration. A joint agreement may be explicit, implicit, or social. An implicit commitment is one we just “fall into” and begin doing with another person. A social contract may be that which holds among group members: to take care of one another, for example, if an old lady falls down in the street then those in the vicinity will rush to her aid.

A joint agreement structures the collaboration (Tomasello, 2016). The agreement states, we will do X and Y and Z. Hence, it is a source of normativity: it tells us what we should do. Strategically, every time we make an agreement, we place our reputation or cooperative identity at risk of damage, if we fail to keep the agreement. A cooperative identity is defined as my reputation with specific individuals with whom I have cooperated in the past (Tomasello, 2016). My fear of losing my good reputation or cooperative standing polices my behaviour with regard to the contract and the cooperation. I need a good reputation and cooperative identity so that people will want to collaborate with me in the future. There are many other sources of collaborative normativity (Perry, 2023).

If any partner in a collaboration wishes to opt out of the original contract, then this requires an additional agreement between all parties (Tomasello, 2019): I must officially “take leave” if I wish to end the collaboration.

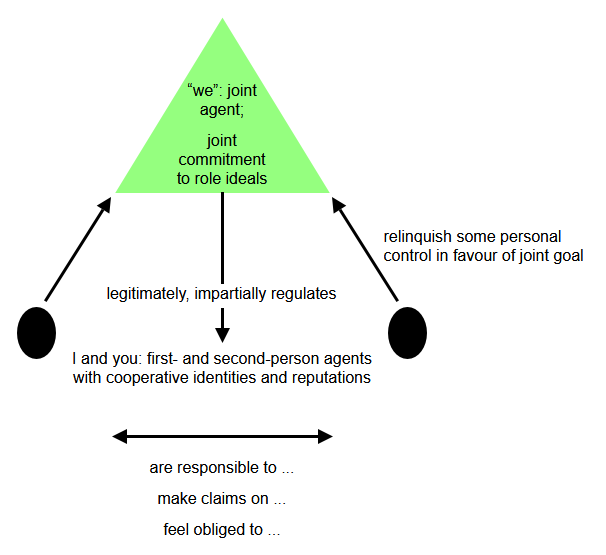

When we make an agreement to collaborate, we are committing to excellent work: to

fulfilling the “role ideals” or ideal standards associated with our roles (Tomasello,

2016). We form a “we”, a joint agent, a partnership. “We” govern and regulate “you”

and “I” on behalf of “us”. This regulation is legitimate (because we each agreed

to it) and impartial (because all partners are functionally interchangeable from

the point of view of “we”: each role may in principle be carried out by any competent

person (“self-

The evolutionary contractualist theory of morality of André, Fitouchi, Debove, and

Baumard (2022) states that I will only cooperate with you if it is worth my while.

So far, so good. I would think that “worth my while” means that we will achieve

our joint goal and so I will be better off than if I had not cooperated. But their

interpretation is that I want to maximise my short-

I will achieve a good reputation as a cooperator if I actually am a good cooperator.

My object in cooperating is to achieve the joint goal, and a good reputation is

a by-

Evolved moral emotions

Obligation has a peremptory, demanding force, with a kind of coercive (negative) quality: I don’t want to, but I have to. Failure to live up to an obligation leads to a sense of guilt (also demanding and coercive). Unlike the most basic human motivations, which are carrots, obligation is a stick.

Tomasello (2019:1)

This quote refers to the fact that I have to do my duty, even though I am lazy and selfish, otherwise I will be punished because: 1) my long term reputation will suffer; 2) we will not achieve the joint goal; 3) my partners will proximately be upset and angry with me. This is the “stick” of cooperative obligation. Yet we also wish to do right by our partners for their sake and for its own sake, impartially. I suggest that this positive wish is evolutionarily based on a reward: the “carrot” of receiving help from my partner to achieve the joint goal which is also my goal. The motive described by André et al. is strategic, and remains strategic in the present day without becoming moral.

Tomasello (2016) proposes that cooperative behaviour began life, in ancient history,

as strategic (non-

What moral emotions would evolve as a result of the formulation of André et al. (2022)?

Hypocrisy: cynical conniving to be as bad as I can get away with without getting

caught. The evolved result would be a lopsided caricature of modern impartial other-

I propose that ancient dependence of people on their cooperative partners led to

the evolution of other-

Ecological validity

The model of André et al. (2022) just does not seem ecologically valid according

to what we know about the lifestyles of modern free-

References

André, Jean-

Perry, Simon – “Understanding morality and ethics” (2021); https://orangebud.co.uk/Understanding%20morality%20and%20ethics.pdf

Perry, Simon – “Foundations of evolutionary ethics” (2023); https://orangebud.co.uk/foundations.html

Tomasello, Michael – “A Natural History of Human Morality”; Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA, 2016

Tomasello, Michael – “The moral psychology of obligation”; Behavioral and Brain Sciences

43, e56: 1-