Other-

... joint intentional activities ... have a unique social-

These early joint intentional activities ... spawn some new dimensions of social

relatedness. If we as collaborative partners are equally necessary for our joint

success, and if we could switch roles and still be successful, and if we both adhere

to the same criteria in playing a role, then we must be somehow equivalent or equal

as partners. This recognition of self-

Following the lead of contractualist moral philosophers, then, our working hypothesis

is that the evolutionary and ontogenetic roots of human morality lie in cooperative

activities for mutual benefit: "The primal scene of morality is not one in which

I do something to you or you do something to me, but one in which we do something

together" (Korsgaard 1996, 275). Participation in joint intentional activities results

in individuals who treat their partners as equals, with mutual respect, because joint

intentional activities are structured by the joint agent “we,” which creates a new

kind of social relationship between “I” and “you” (perspectivally defined) as constituents

of that “we”. That is to say, participation in joint intentional activities creates

the conditions for what philosophers call second-

... The relationship between partners has now become normative; each feels obligated to honor her commitment by responsibly playing her role and accepting her partner's criticism as legitimate if she does not.

Michael Tomasello – “Becoming Human -

References in text:

Korsgaard, C. 1996. The Sources of Normativity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Darwall, S. 2006. The Second-

Introduction

Other-

We hypothesise that cooperation is the preferred option when benefits can optimally be achieved mutually rather than alone or competitively (André, Fitouchi, Debove, and Baumard, 2022).

As with any species, the environment shapes the evolution of human behaviour and

emotions. The idea of other-

Risky foraging niche

=>

- obligate cooperative breeding

- obligate sharing

- obligate collaborative foraging

This evolutionary scenario, we propose, explains empathic concern towards non-

Simplified time line:

The ancestors of the genus Homo (i.e., great apes) were, we believe, already sociable, intelligent, and using tools.

... as the genus Homo was emerging some 2 million years ago, a global cooling and drying trend created an expansion of open environments and a radiation in terrestrial monkeys, who would have competed with Homo for many plant foods. Scavenging large carcasses killed by other animals would have been one possible response. Such scavenging would have required multiple participants, as other carnivores would be competing for those carcasses as well.

Tomasello et al. (2012) – Two Key Steps in the Evolution of Human Cooperation: The Interdependence Hypothesis

From 2 million years ago: cooperative scavenging, cooperative breeding, generalised sharing, generalised care, discouragement of hogging and stinginess and laziness. Cooperative breeding means to share the feeding and care of children within a small group. It is likely to increase the reproductive success of I, the individual, if I enlist other adults to help look after and feed my children. See: Perry (2021:173).

From 500,000 years ago: cooperative hunting of large game.

From 150,000 years ago: emergence of large tribal cultural groups that were separated into small associated bands.

From 10,000 years ago: distributive justice and free rider control; procedural justice. This is approximately when humans began to give up the nomadic way of life, living and surviving with friends and family, and to settle in large, culturally mixed, personally anonymous city states. There has been a great deal of relatively recent human evolution, even in the past 5,000 years (Subbaraman, 2012).

The actual picture may be much more complicated (Singh and Glowacki, 2022). However,

we hypothesise a long period (~1.5 million years) when human ancestors lived in small

mobile egalitarian bands with an immediate-

Cooperative breeding, and sharing, are other-

Fairness

Collaboration towards win-

=>

joint agent “we”

=>

- interdependence (generates empathic concern, and shapes normativity)

- mutual risk

- self-

other equivalence (generates impartiality and equality) - first-

and second- personal agents (myself and the partners who work with me) - mutual value

- mutual respect

- mutual deservingness

- mutual obligation (to help and respect each other)

- mutual responsibility (to fulfil ideal standards)

Being fair is not the same as being nice. If I am extra nice to one person by giving her more resources, that nevertheless might be unfair to others. But if the recipient needs the resources more, or is somehow responsible for more of the resources being available (for example, she did more work), then perhaps it might be fair after all. The judgment of fairness is thus always grounded in some judgment of equality – equal resources per person, or per unit of need, or per unit of work effort, or whatever – with the self being treated, impartially, as equivalent to others (in terms of deservingness). A sense of fairness naturally comes with a sense of obligation: everyone including oneself should get what they deserve. A sense of fairness thus competes, in some circumstances, with both selfish and generous motives.

– Tomasello (2019:232-

Young children first start to show a sense of other-

Other-

We hypothesise that other-

Regarding this, there are two significant differences between chimpanzees and humans:

1) chimpanzees do not like to share resources, unless strategically with coalitionary

partners; 2) chimpanzees are self-

Partners expect and demand to be respected as equals during and after collaboration, and anything less is sure to be met with social resentment and indignation (Tomasello, 2016, 2019). Instead of being treated fairly, I have been exploited, cheated, bullied, or ignored.

Why do we typically feel a sense of reward when we treat our partners fairly? It may be satisfaction at all the deserving partners impartially getting what they deserve; satisfaction at (distributive or procedural) justice having been done; that things have been done right.

So, deciding what is fair to me is not (only) a matter of “what I can get away with,

without others protesting or thinking too badly of me” (André, Fitouchi, Debove,

and Baumard, 2022): it is perhaps more accurately a matter of impartially giving

each partner what they deserve, given self-

Step 1: generalised sharing; step 2: distributive justice

Why do humans enjoy sharing so much – whether hospitably, collaboratively, or in response to need? The answer is probably our risky foraging niche, where, in ancient times, to be part of a personal sharing network was to survive.

Sharing is a way of “pooling risk”: it is a social insurance for every participant and beneficiary. When I go out hunting, there is the risk I will catch nothing. When I catch nothing, my group will share with me; and vice versa. The benefits of living in a sharing network are mutual over time.

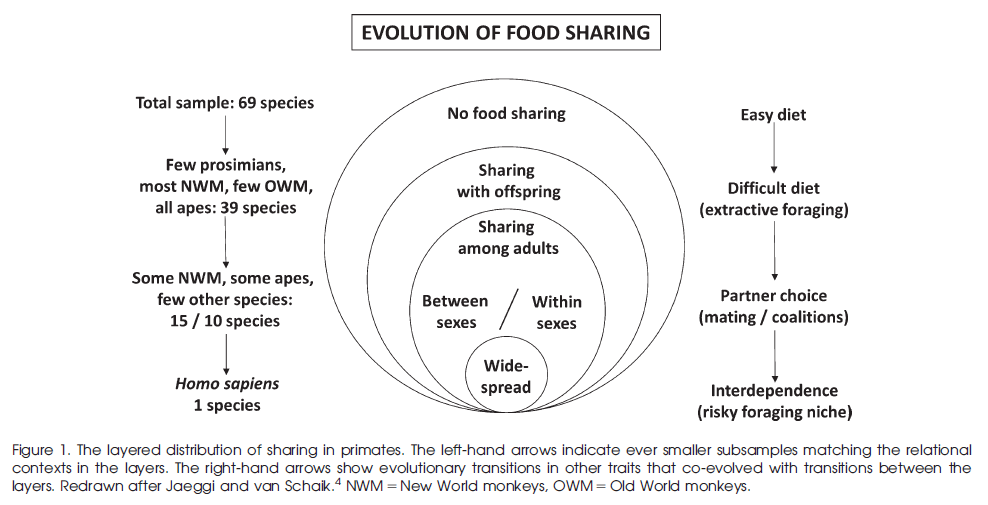

The diagram below is from Adrian V Jaeggi and Michael Gurven – “Natural Cooperators:

Food Sharing in Humans and Other Primates”: Evolutionary Anthropology 22: 186-

Immediate-

In the classical model (Woodburn, 1982), immediate-

Batek regarded each other as basically equal in their intrinsic value and therefore worthy of respect. Although some people, particularly shamans, were held in especially high regard, they neither expected nor received special treatment from others. All Batek felt that they deserved the same consideration as everyone else, and they were not shy in saying so.

Kirk M Endicott and Karen L Endicott – “The Headman was a Woman – The Gender Egalitarian Batek of Malaysia” (2008)

We know that some modern hunter-

Given that there was a shift, at some point early in human history, from the great

ape competitive way of life based on dominance hierarchies to a cooperative, prosocial

way of life, in a process known as self-

Most non-

- from immediate-

to delayed- return economies - from communal sharing to private hoarding (and distributive justice)

- from personal autonomy and egalitarianism to dominance hierarchies

The claim is that partners within a collaborative joint agent know cognitively that

they are equivalent in a number of ways including value and status (Tomasello, 2016,

2019). This is called self-

This implies that fairness evolved in the continued presence of cognitive self-

From the “bird’s eye view” of the joint agent’s perspective, within each role, the partners are interchangeable.

Following Tomasello (2019:191): self-

- “If we as collaborative partners are equally necessary for our joint success ... ”

Each is equally necessary, but not sufficient on their own, for joint success. This implies mutual utility and value.

- “... and if we could switch roles and still be successful ... ”

This implies mutual value and recognition of status: each partner is good enough to fill each role. It also implies a sense of equivalence.

- “... and if we both adhere to the same criteria in playing a role ... ”

This implies mutual recognition of status, since each person’s competitive, self-

- “... then we must be somehow equivalent or equal as partners. This recognition of

self-

other equivalence generates a mutual respect and sense of equality among (potential) collaborative partners.”

Some of the reasons for self-

The human paradigm of cooperation and its corollary, self-

Examples of self-

- I am one among many.

- That could be me.

- How would you like it if I did that to you?

- If I were in your position I would have done the same thing.

I feel obliged to treat my collaborative partners with respect and fairness because: 1) we are all equivalent; 2) we are all deserving; within the joint agent “we”. After a successful collaboration, “we” are all deserving because we have all fulfilled our roles working towards the joint goal, and I benefit from this personally because the joint goal is also my goal.

The normativity – pressure of shouldness – of the obligation to treat collaborative partners respectfully and fairly is thus derived from: 1) your biological pressure to thrive; 2) your need and expectation that this will be respected, especially as you know that you are a valuable partner of good standing; 3) our pressure to achieve the joint goal; 4) my pressure to retain you as a partner; 5) my pressure to maintain a good cooperative identity/reputation for the long term (i.e., for my partners to think well of me).

I am normatively obliged to help my collaborative partners because this is helping “us” (myself and the other partners) to achieve our joint goal(s).

See also: Responsibility (below)

... during human evolution, great apes' sympathy for kin and friends evolved into humans' sympathy for a wide variety of others, initially for collaborative partners and then for everyone in the social group. Modern infants have inherited both versions.

Tomasello (2019)

... friends in the stone age depended on one another for their very survival. Humans

lived in close-

“Were we happier in the stone age?” – The Guardian, UK, 5th September 2014

Humans’ sense of empathic concern for other humans evolved in the context of living in small interdependent groups. Chimpanzees and bonobos show some empathic concern for each other, and will help others if the cost is not too great, but they have zero sense of fairness (Tomasello, 2016, 2019). They are somewhat interdependent, while humans, living in our risky foraging niche, are highly interdependent with and valuable to each other, and consequently, feel more general empathic concern. If you are valuable for my existence, then as a normal person, I will develop towards you: 1) a sense of empathic concern; 2) a warm positive regard.

In essence, this small-

Emotions can be seen as psychological reactions to fitness opportunities or threats (Perry, 2021). As such, empathic concern can be seen as my emotional reaction to someone else’s goals being thwarted. Empathic concern is rather fragile and can easily be switched off if we dislike, disapprove of, or are competing with the other person (Decety, 2011).

Empathic concern evolved in the context of parental care in mammals (and birds), and so, naturally, it is linked in the brain to social attachment and taking action (Decety, 2011).

The Golden Rule

... people are much more likely to experience [the] altruistic motive when another

person’s welfare is made emotionally salient to them by empathic perspective-

Dill and Darwall (2014:13)

Chimpanzees will adopt the perspective of a competitor, seeing the world through their eyes, in order to find out what they are “up to” (Tomasello, 2019). In other words, their motive for perspective taking is largely Machiavellian and competitive.

The human social world is one of multiple perspectives, as each person has their own perspective onto our common ground. Humans will readily combine empathic concern with “imagine self in position of other” perspective taking, and this is what we call the Golden Rule: “I feel empathic concern for myself (or a loved one)”; “I see myself/them in you” => “I feel empathic concern for you”.

It is stressful for us to acknowledge someone else’s suffering unless we then resolve and are able to take action (Perry, 2021:157).

Reciprocity

Reciprocity is related to fairness. Both are examples of a fundamental mode of human

interaction that Fiske (1991) calls “equality matching” (the other three are “communal

sharing”, “authority ranking” and “market pricing”). In reciprocity, I give you

what I feel you deserve, in response to something you have done. In some cases,

this is the result of a contract or agreement to exchange goods or services of equal

value. We do this impartially and self-

Three common forms of reciprocity are tit-

Responsibility

For me to exercise responsibility means to uphold the ideal standards associated with my role; to behave responsibly; to be a responsible collaborative partner. It means to turn in excellent work and to do my duty. These role ideals carry a normative pressure to achieve them, which is derived ultimately from the universal biological pressure to thrive (achieve goals).

As well as being a normative obligation towards the self and others, responsibility is another word for accountability. To take responsibility also means to shoulder a burden of duty (to achieve role ideals).

I am responsible to myself and my collaborative partners, the joint agent, in which

“we” collaborate to impartially regulate “you” and “I” on behalf of “us” in the direction

of 1) achieving the joint goal; and 2) fulfilling our obligations of helping, respect

and fairness towards each other. This collaborative-

Each partner’s role ideals are sub-

The normativity of responsibility is therefore derived from the instrumental normativity of the joint goal and the social normativity of respect and fairness towards others (animated by the pressure to achieve social well being). Normativity is here defined as the pressure to achieve goals in general.

... moral obligations are represented as legitimate interpersonal demands

Dill and Darwall (2014:24)

When we make a commitment to collaborate, we form a joint agent “we”, and you and I identify with “us” (our goals are aligned). Each of us thereby relinquishes some personal control in favour of the joint agent, and this joint control is directed interpersonally as normative pressure given and received between partners to be diligent, skilful, etc.: 1) for the sake of our joint goal; and 2) because each partner is taking a risk by relying on the other – thereby threatening their personal well being.

Partner control and accountability

Partner control means attempting to turn a poorly performing partner (the self or others) into a well performing partner (Tomasello, 2016).

If partner A feels that he has been treated unfairly, unjustly or disrespectfully by partner B, he can make a “respectful protest” towards partner B, informing her of his resentment but respectfully assuming that she is a cooperative person who wants to maintain her cooperative identity. If partner B is still behaving poorly after this, then partner A always has the option to change partners (partner choice), and partner B will run the risk of damaging her own cooperative identity in the process. A cooperative identity is my standing with my cooperative partners, past or present.

... moral anger drives its subject towards a unique goal: to make the wrongdoer hold himself accountable to the moral demand he flouted.

Dill and Darwall (2014:14)

To hold someone accountable is to press the demand that they fulfil their responsibilities, through protest, blame, reproach, indignation, condemnation, or punishment (Dill and Darwall, 2014).

Guilt means to turn the respectful protest upon oneself (through self-

First and foremost, guilt leads its subject to take responsibility for her wrongdoing

... . Second, guilt motivates its subject to make amends with the victim of wrongdoing

by apologizing ... , making reparations ... , striving to correct future behavior

... , and even self-

Dill and Darwall (2014:26)

If the offender agrees to hold him-

What is the motive driving morally conscientious behavior? When we “do the right thing,” what are we trying to accomplish?

Our answer to this question is that morally conscientious behavior is driven by the moral conscience; an intrinsic desire to comply with moral demands to which one may be legitimately held accountable, or equivalently, to comply with one’s moral obligations. This is the accountability theory of moral conscience.

Dill and Darwall (2014:14)

The conscience looks both forwards, by regulating future behaviour, and backwards,

with guilt, self-

We are obliged, and accountable, to ourselves, and our partners, to achieve the joint

goal and its subgoals (i.e., there is normative pressure to do so). This is true

even if our partners are fellow members of our large group, and our joint goal is

thriving and surviving together (win-

Forgiveness

Forgiveness is an aspect of reciprocity. If you and I are taking turns to “cooperate” and you suddenly “defect” (let me down) then I have two rational options: I can forgive you, with appropriate conditions on your part, and carry on our cooperative relationship; or defect in kind, effectively ending the partnership.

Reciprocity can be studied using computer simulations. Two computer-

The winning strategy has been found to be “hopeful, generous and forgiving”. “Hopeful” means that you need to start the interaction by being cooperative, and hope that this will encourage the other party to cooperate in return. “Forgiving” means that if the other person defects, you will work hard to rebuild a working relationship of cooperation. “Generous” means not to be too worried about getting exact returns for what you have put in, but instead be pleased to be engaged in a cooperative relationship where everybody benefits.

On the computer it is found that if you forgive 100% of the time, cooperation quite quickly falls apart and this is not a successful strategy. If you always forgive bad behaviour, there is no incentive for the badly behaved person to behave well, and since they are not interested in mutual cooperation, the working relationship cannot continue.

Conflict minimisation

Conflict is costly for both sides, including the winner. Conflict minimisation is

another way to achieve win-

Generalised care in humans

The African Painted Dog or African Wild Dog is a cooperative carnivore like humans, that lives in a similar foraging niche as ancient humans (African savannah, woodland), uses cooperative breeding (with the dominant pair breeding only), and feeds their old, sick or injured members who cannot hunt (Born Free, 2023).

There is archaeological evidence of ancestral humans caring for their sick and injured going back up to 1.6 million years ago in Homo erectus (Spikins, 2015) and increasing in frequency as we get nearer to the present day. This has been a great puzzle for evolutionary anthropologists. Perhaps the answer is that cooperative health care is part and parcel of an ethos of cooperative breeding, communal sharing and cooperative empathic concern, together with the Golden Rule: “that could be me”.

Natural selection works on every individual’s relative advantage compared with others; hence, gaining an absolute benefit is insufficient. If individuals were satisfied with any absolute benefit, they might still face negative fitness consequences if they were doing less well than competing others. It makes sense, therefore, to compare one's gains with those of others.

Sarah F Brosnan and Frans B M de Waal – “Evolution of responses to (un)fairness”

- achieving fitness benefit => pleasure

- fitness benefits are both absolute and relative

- achieving relative fitness benefit over others => pleasure

D, the Dark factor of personality, is defined as

the general tendency to maximize one's individual utility – disregarding, accepting, or malevolently provoking disutility for others –, accompanied by beliefs that serve as justifications.

Moshagen, Hilbig, and Zettler (2018)

or: thriving at the expense of others.

The “Dark factor” theory of personality states that all the varieties of “dark” behaviour

share a common “dark” core, defined above. Some of these include controlling behaviour,

egotism, a sense of entitlement, grandiosity, Machiavellianism, moral disengagement

(ignoring morality), sadism, self-

Narcissistic personality disorder, anti-

Not everyone who is on the spectrum has a disorder. Behaviour is classified as disordered when it harms the self or others. For example, a narcissist may believe they are better than everyone else and that they deserve special treatment; but if they have a full complement of normal empathic concern, and they don’t atypically hurt themselves or others, it is not a disorder. Conversely, we are all capable and guilty of “dark” behaviour.

By definition, a personality disorder is the name for:

A repetitious and relatively inflexible maladaptive pattern of thinking and behavior that starts in childhood and continues into adulthood. It is stable across most situations and is expressed in most relationships. It limits people's ability to react in a flexible and spontaneous way to new people and new situations.

“Narcissistic Personality Disorder” is the name of one of those patterns.

Elinor Greenberg (2018)

There is controversy over whether narcissistic and other Cluster B personality disorders

are genetic disorders of interpersonal relations (which I agree with) or learned

adaptations to difficult childhood situations (Greenberg, 2016). I view NPD as a

disorder of cooperation whereby the individual is fundamentally self-

Greenberg (2016) identifies three kinds of narcissists:

- covert or closet

- exhibitionist

- toxic or malignant

We may add a fourth kind: a sub-

The various kinds of narcissists are defined by how they achieve their competitive advantage over others. Exhibitionist narcissists are primarily concerned with status and how they appear to others. Malignant or toxic narcissists are primarily concerned with hurting others.

A psychopath, even without the emotion of empathic concern, is capable of helping

others when necessary (e.g., Walker, 2019c; 2021). Athena Walker, a self-

Importantly, in the scientific literature and popular culture, psychopaths are confused

with narcissists and people with ASPD. This may be because they are self-

At the other end of the spectrum of prosociality, there is a minority of “extraordinary altruists” (Marsh, 2017) who are unusually caring, generous and altruistic. Around 40% of people possess both the normal “light” and a significant “dark” personality profile. These “dark” traits damage relationships and hold people back in life (Neumann and Kaufman, 2020).

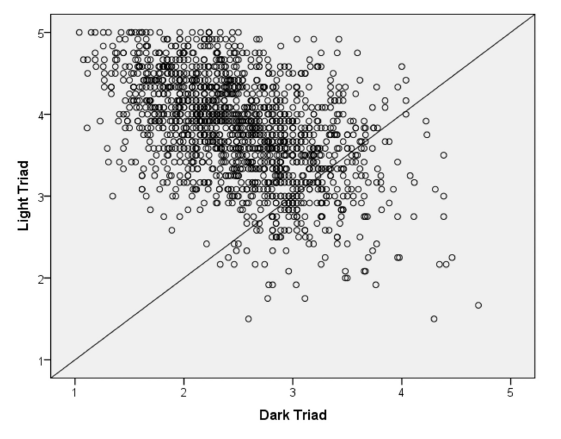

Scatter plot of the (dark, light) scores of 1518 people (Kaufman, Yaden, Hyde, and Tsukayama, 2019). These data suggest that people are mostly “good” (i.e., most data points are in the top left of the diagram) and that extreme malevolence is rare (bottom right of diagram).

References

André, Jean-

Baskin-

Born Free (2023) – https://www.bornfree.org.uk/animals/african-

Brosnan, Sarah F and Frans B M de Waal – “Evolution of responses to (un)fairness”: Science vol 346, issue 6207, 17 October 2014

Cooper, J E (editor) – “Pocket Guide to the ICD-

Curry, Oliver Scott; Daniel Austin Mullins; and Harvey Whitehouse – “Is It Good to

Cooperate? Testing the Theory of Morality-

Decety, Jean – “The Neuroevolution of Empathy”: Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1231, 2011

Dill, Brendan; and Stephen Darwall – “Moral Psychology as Accountability”; [In Justin

D’Arms & Daniel Jacobson (eds.), Moral Psychology and Human Agency: Philosophical

Essays on the Science of Ethics (pp. 40-

Endicott, Kirk M and Endicott, Karen L – “The Headman Was a Woman – The Gender Egalitarian Batek of Malaysia”; Waveland Press, Long Grove, Illinois 2008

Fiske, Alan – “Structures of Social Life: the four elementary forms of human relations"; Free Press, New York 1991

Greenberg, Elinor – “Borderline, Narcissistic, and Schizoid Adaptations – the pursuit of love, admiration, and safety”; Greenbrooke Press, New York 2016

Greenberg, Elinor – https://www.quora.com/Why-

Kaufman, Scott Barry; David Bryce Yaden; Elizabeth Hyde; and Eli Tsukayama – “The Light vs. Dark Triad of Personality: Contrasting Two Very Different Profiles of Human Nature”: Frontiers in Psychology, 10:467, 2019

Marsh, Abigail – “Good for Nothing – from altruists to psychopaths and everyone in between”; Robinson, London 2017

Moshagen, Morten; Benjamin E Hilbig; & Ingo Zettler – “The Dark Core of Personality”:

Psychological Review, Vol 125(5), 656-

Neumann, Craig and Scott Barry Kaufman – “Are people with dark personality traits

more likely to succeed?”; https://psyche.co/ideas/are-

Perry, Simon – “Understanding morality and ethics” (2021); https://orangebud.co.uk/Understanding%20morality%20and%20ethics.pdf

Perry, Simon – “Foundations of evolutionary ethics” (2023); https://orangebud.co.uk/foundations.html

Singh, Manvir; and Luke Glowacki – “Human social organization during the Late Pleistocene:

Beyond the nomadic-

Spikins, Penny – “How Compassion Made Us Human – the evolutionary origins of tenderness, trust and morality”; Pen and Sword Archaeology, Barnsley, South Yorkshire 2015

Subbaraman, Nidhi – “Past 5,000 years prolific for changes to human genome”; Nature, 28 November 2012; https://www.nature.com/articles/nature.2012.11912

Thomas, Rachel – “Does it pay to be nice? – the maths of altruism part i”; 2012;

https://plus.maths.org/content/does-

Tomasello, Michael; Alicia P Melis; Claudio Tennie; Emily Wyman; Esther Herrmann – “Two Key Steps in the Evolution of Human Cooperation – The Interdependence Hypothesis” – Current Anthropology, vol. 53, no. 6, Dec 2012

Tomasello, Michael – “A Natural History of Human Morality”; Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA 2016

Tomasello, Michael – “Becoming Human – a theory of ontogeny”; Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA 2019

Walker, Athena – “Do psychopaths not feel emotions or do they suppress them?”; 2019a

https://www.quora.com/Do-

Walker, Athena – “What would be the difference between a mature psychopath and an

immature psychopath?”; 2019b; https://www.quora.com/What-

Walker, Athena – “Will a psychopath purposely not hurt someone’s feelings solely

because they feel it would be illogical to do so?”; 5 July 2019c; https://www.quora.com/Will-

Walker, Athena – “Would a psychopath help out a person in need? If so, what would

be your motivation considering empathy is not in play? For example, if you saw a

lady fall unconscious in the sun.”; 16 May 2021; https://www.quora.com/Would-

Woodburn, James – “Egalitarian Societies”: Man, New Series, Vol. 17, No. 3, pp. 431-